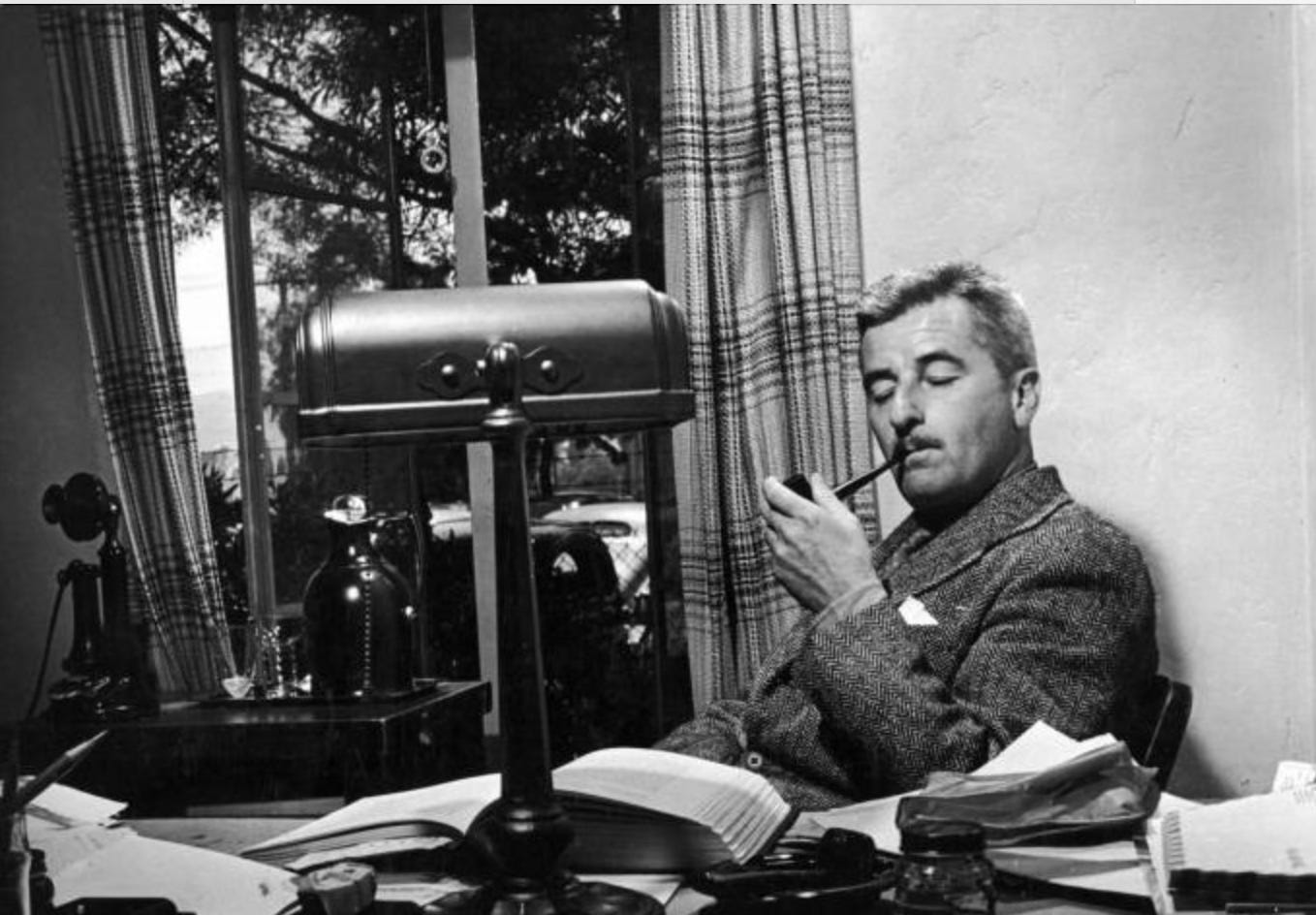

Redeeming Faulkner from Hell

A Different Perspective on Authorial Style

I usually dick around on Substack while I have my morning coffee, reading whichever essays or pieces of fiction catch my eye while scrolling through the Notes section of the app. This morning, I happened to find an older piece by Thaddeus Thomas, a friend of mine who writes The Literary Salon, which is all about the craft of literary writing. To Hell with William Faulkner is a thought-provoking piece on the topic of authorial style. I mostly agreed with what Thaddeus wrote, but the essay inspired me to add some context of my own to the discussion.

Before I get into it, I have to expend a few paragraphs on my bona fides. I am decidedly a nobody in the publishing world, yet despite my nobody-ness, I’ve managed to make a pretty good living writing fiction full-time for over a decade now, and I’ve been writing literary fiction exclusively for eight of those years.

I am among the unluckiest writers I know. My failures are constant and relentless, and the success I’ve managed to build has come from an even more relentless will to succeed. I have long since lost count of the number of times I’ve picked myself up and kept going after all the numberless doors have slammed in my face. However, I did have one important stroke of good luck in my life, and that was being born into a family of professional artists. From my earliest memories, I’ve had a front-row view of what it takes to turn art into a well-paying career. That may be why I’ve been so dogged about picking my ass up after all the many, many times I’ve been knocked down. I grew up with an innate acceptance of the fact that it’s a very long and very brutal path to carve out and nurture a career in the arts. Stubbornness and an unshakable belief in yourself are the two traits that will serve you best, in the end.

Observing how the arts work from my earliest childhood gave me a lot of insight, for which I am grateful. It didn’t matter that I was spawned by a bunch of painters but knew from the time I started talking that I was going to be a writer. The principles of art are the same, whether your art is visual or musical or performative or written. Only the media differ.

One of the lessons I learned very early—before I was even writing in a serious, focused way—was that if you want to make a living from your art, you’ve got to find some way to give it commercial appeal. So though I’ve always wanted to write literary fiction for a living, I knew that I needed to find some way to couch that literary essence within a more easily marketed genre. Thus, my popular pen name, Olivia Hawker, is known for historical fiction… but if you’ve ever read my work, you know it’s literary as hell.

(Side note: I’m transitioning from literary historicals to literary sci-fi as the cultural zeitgeist shifts. I stay on my toes and move with the market, which is what you have to do if you want to keep the money coming in. Another valuable lesson I learned from my family of painters.)

Voice emerges in its own time. It can’t and won’t be rushed. It is a stage of artistic maturity, achieved through long practice and dedicated study of your art form.

I’ve also been quite generously compared by reviewers to three of the authors mentioned in Thaddeus’s essay. I won’t tell you which ones, because that would feel like bragging. I was flattered and pleased by the comparisons each time, and also pretty saddened, because the odds that I will be remembered at all are slim, and the odds that I’ll be remembered as one of the greats, like those fellows in Thaddeus’s essay, might be a fraction of a hair above zero. That’s another lesson I learned from a lifetime in the pro-art world. For every Van Gogh, there are a thousand more undiscovered geniuses whose work is never appreciated, either during their lifetime or after. The skeleton of Herman Melville got really lucky when the unique brilliance of Moby-Dick (which, in my opinion, is one of the greatest novels ever written) achieved full appreciation decades after he kicked the bucket.

So all of this rambling about my past and my career is to establish the fact that I have enough experience with both the business end of writing fiction and the artistic end to justify the addition of my own points to those Thaddeus made in his essay on style. I am barely known at all, and not nearly as acknowledged as I would like to be (a fact which haunts me daily and spurs the most brutal of my depressive swings) but what little reputation I do have comes down to my command of style.

(NB: I use the words “style” and “voice” interchangeably in this essay.)

I do a lot of speaking at writers’ conferences, sometimes as a keynote, sometimes as a masterclass presenter, sometimes just as a panelist. I don’t believe there has ever been a Libbie-talks-at-a-conference situation where the subject of voice or style wasn’t raised. I’ve even occasionally been ambushed in public restrooms by wild-eyed young writers who find it so urgent to pick my brain on style that it can’t wait until after I’ve had a pee. It’s a subject that gnaws at newer writers, and understandably so. Style is what makes writing unique. It’s what defines the stand-outs who are remembered and lauded, as Melville and Faulkner and Hemingway and McCarthy are remembered (and let’s add some female writers to the list of lauded stylists: George Eliot, Jane Austen, Edith Wharton, Toni Morrison, Virginia Woolf, Joan Didion, Hilary Mantel, Ali Smith, Kathryn Davis, Louise Erdrich, and the untouchable high priestess of voice herself, Zora Neale Hurston.)

When newer writers ask me about style—how to define it, how to develop it—my answer is always the same: I don’t believe that style is something that can be deliberately cultivated. In that respect, William Faulkner was right, and his spooky Southern-gothic ghost doesn’t deserve all the “go to hells” that Thaddeus threw at him in his essay.

In fact, I think what Faulkner asserted is true—that a writer who’s more concerned with placing emphasis on their style probably doesn’t have all that much to say, and they probably know they’ve got nothing to say. The insecurity of not understanding one’s own point of view, or the lack of courage to forthrightly communicate that point of view, does tend to make one cling to style as a kind of life raft. Style becomes this crucial buoyancy that will keep the developing writer afloat long enough to prove that what they’re producing is worth a damn (or so the new writer hopes.)

I speak from experience on this, and without any judgment. This awkward “holy shit, what do I do? Better pile on the style super hard!” phase is a natural stage of development that all writers must experience. It’s part of learning how to be a writer who does, in fact, produce stuff that’s worth a damn. I look back at most of my early writing and it’s so over-the-top that I cringe and die and the particles of my physical substance melt into whatever was below me when I fell, and all evidence of my existence is thoroughly erased by my own retrograde embarrassment.

If you want to really find your authentic voice, you need to let go of the fear of judgment.

Here’s what I always tell new writers about voice, because it’s what I’ve learned about the subject through decades of experience: What a makes a writer’s voice memorable are its unique qualities. And impersonation, by definition, is not uniqueness. You will never successfully cultivate voice because the only way to cultivate it is through mimicry of other authors—authors who aren’t you. Deliberate cultivation of voice does not yield unique results, and when it comes to voice, uniqueness is the only thing that matters.

That’s not to say that there’s no value in deliberately copying or adapting another author’s style as a creative exercise. In fact, this is another important trick I picked up from a lifetime of exposure to the arts. Trying to mimic a better artist’s style is a fantastic way to learn more about the craft of your particular medium. Painting replicas of masters’ works has been an important part of visual arts education for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. Want to get really great at guitar? Spend months trying to duplicate that one solo Mark Knopfler played at the Hammersmith Odeon in 1984. The practice of deliberate mimicry will teach you a lot of important lessons about technique, mostly because it requires you to slow down and think about what you’re doing, to get critical and selective in your word choice, to pay attention to rhythm and harmonics and balance, which are probably aspects of craft you never even thought about before.

But though such practices are great for solidifying other aspects of your craft, I still maintain that they will not help you develop your authentic voice.

Voice emerges in its own time. It can’t and won’t be rushed. It is a stage of artistic maturity, achieved through long practice and dedicated study of your art form. Voice is maturity of thought, too—the ripening of certain ideas that are central to you, the themes and imagery that return to the surface of your work time and again, the lexicon of symbols that resonate in your soul. An author’s voice is that author’s unique personality finding self-expression through words. You cannot carve up the authors you most admire and Frankenstein them together in bits and pieces to force the creation of “you.” The only way to find out who you are as a writer and as a person is to spend a whole hell of a lot of time in honest thought, and in monastic dedication to your art, even in the early stages when it’s rough and dissatisfying and hangs awkwardly from your frame because nothing fits yet, because you don’t yet have the skills to tailor down the excess into a fine suit you can wear like your own skin.

Yet Thaddeus wasn’t wrong in his essay, either. In the “Rules of Style” section, he makes some very wise and useful points.

Our bad habits, so desperately clung to in our early years of development, are not our style. They’re just bad habits. Every great visual artist started out as a child who colored outside the lines. Gradually, we learn how to color with more control, to make deliberate choices that better represent the ideas we are trying to convey. Eventually, we might return to an “outside the lines” approach in order to make a specific statement, but by that time, we know what statement we wish to make and we have developed a host of foundational skills that allow us to color outside the lines with deliberation and purpose, to heightened artistic effect. No new writer should believe that their early efforts are masterpieces of style. They might be pretty darn good for the work of a new writer, but believe me, your early stuff isn’t anywhere near as good as your work will be a decade on, or two decades on. Accept that your early work has plenty of room for improvement. I promise you, it does, no matter how much it impresses you at this point, no matter how favorably it may compare to the work of other new writers.

I actually disagree with Thaddeus that talent is skill. I think some people are, in fact, born with natural aptitudes for certain kinds of art, and those people need relatively less work and refinement to take their native talent to the level where one can expect to make some money from that art, or to build an eager audience.

However, talent doesn’t matter nearly as much as skill does. Skill will take you as far as natural talent will, and maybe even farther. More to the point, I defy anyone to tell the difference between art produced by a naturally talented person and one who worked their ass off to build their skills. It’s an irrelevant difference when the chips are down, so you should spend exactly zero moments of your life fretting over whether you’re a naturally gifted writer or not. It doesn’t matter. Put in the work to learn your craft, and nobody will be able to tell the difference.

Thaddeus’s third rule is that style is the aesthetic of obeying and disobeying literary rules in a cohesive and pleasing matter. I think that’s an interesting and fairly accurate way of defining style. I think style is also more than that; I believe it incorporates the writer’s point of view on the world, which is impossible to separate from the circumstances of that writer’s birth and their path through life—their culture of origin, the events of their childhood and early adulthood, the people and places and works of art that have shaped them, even the zeitgeist of the era in which they lived. But “an aesthetic of conforming or not conforming to artistic convention” is probably one of the main crystals from which the rest of an artist’s style grows.

So, as one of those relatively rare people who has managed to turn literary fiction into a full-time career, and as an author who is known for her voice (if it can be said that she’s known for anything, which is debatable) what are my rules of style?

Here they are, for whatever they’re worth. Take ‘em or leave ‘em as you see fit.

Libbie’s Advice on Style/Voice

First, Authentic voice only comes from artistic maturity. Maturation takes time, experience, effort, thought, and more time. It is a natural progression from a Point A to a Point B, and then onward to Points C, D, E, etc. You never reach the end of maturation; you just eventually konk out and expire when your time comes, and then your work has to go on speaking for you after you’ve departed. If you’re lucky. So you should expect your artistic maturation to be an ongoing process that continues over the course of your entire life. Yes, that means your voice will evolve as you gain more maturity. This is good and natural. Change is the only constant in the universe, and all artists should reject stagnation.

Second, Appreciate where you are now and accept it for the necessary stage in your development that it is. No, you probably don’t have an authentic voice yet. And if you have developed an authentic voice through time and practice and maturation, it’ll be different a few years down the line, when you change more and the world changes around you. It is what it is. Artistic development is an ongoing process that never ends. You will never be as good as you will be in the future. Get used to that fact. It will always be true, no matter how long you live, no matter how good you get at making your art.

Now for some real, actionable advice.

If you want to really find your authentic voice, you need to let go of the fear of judgment. I know that’s hard to do in any art form, but the writing world is especially rife with judgment, packed as it is with all the layers and layers unnecessary gatekeepers. It gets a little easier to drop your fear of judgment once you realize (through mournful experience) that almost every one of those gatekeepers can’t tell their ass from a hole in the wall, anyway.

Try things. Experiment. A lot of what you try won’t work at all. A lot of it will suck. Who cares? You won’t die if you write something shitty, I promise. I’ve written mountains of shit while I was in experimental mode (and plenty of shit while I was NOT in experimental mode) and not only am I still alive, but my career is thriving.

You will not discover the unique things only you can do if you’re too afraid of putting a foot wrong to ever put a foot anywhere in the first place.

Rules are for writers who like rules. If rules make you feel safe, then great. You should follow them. But remember that rules also do not allow for unique expression. If you want to find your authentic voice, you won’t find it among the rigid structures of proscribed rules. The rules will make you write like everybody else. They will flatten whatever voice you have been subtly developing and drown it under an ocean of same-same mediocrity that’s indistinguishable from everything else that was published over the last five to ten years.

Think about your craft in ways other writers don’t think about theirs. One of the features that makes my voice stand out is my use of sound. Despite being printed on a page, my work has a distinctly auditory quality. Most writers put their sentences together with a single purpose in mind: to convey information to the reader. And that’s fine. It works really well for a lot of writers. Mine is unique because I don’t just convey the particulars of plot and character; every sentence and paragraph and scene are sonic compositions that use auditory features like rhythm, tempo, consonance and assonance, internal rhyme, alliteration, repetition, and coda to add a subtle layer of emotional manipulation to my scenes. My stories aren’t just stories; they’re deliberate compositions of emotion that the reader feels, and I achieve that effect by applying principles of music to my writing.

You don’t have to do the same thing with your writing (though you sure can, if the idea appeals to you.) There are countless ways to skin a cat, and just because my approach to style works well for me, that doesn’t necessarily mean it will work for you. I arrived at my thesis that “story is a composition made from information and sound in equal measure,” my unique artistic voice, after a couple of decades of intense study and practice of my art form. Those decades of practice and study were informed by aspects of my individual personality—my deep connection to music, including the many years I spent studying music as a child; my personal perspective on storytelling as cultural artifact; my fascination with neurology and psychology and the places where musical theory overlaps with biology and consciousness (whatever consciousness is.)

You might not be as into music as I am, so maybe it doesn’t make sense for you to approach your craft from an auditory perspective. That’s fine. It’s not important that you arrive at the same conclusions about craft that I arrived at. What’s important is that, when you feel ready to let go of “the rules of writing” to forge your own unique path into your artistic practice, you think about that craft in ways that are authentic to who you are as an individual.

Do you know who you are as an individual now?

Are you sure about that?

This, too, is a knowledge that takes time and introspection to develop. The features and circumstances that have shaped you into the person you are differ from the features and circumstances that made William Faulkner into the person he was. Or Zora Neale Hurston into the person she was.

If you want to let your style flourish—or find it in the first place—give yourself the time you need to mature artistically and psychologically. Give yourself time for a deep study of self, an examination of perspective, belief, symbolism, and interest that reveals the warp and weft of your own substance.

And then write whatever is true to what you find inside. If you do that, your voice will emerge without any worry or effort.

This essay rules for a number of reasons:

1. As a fellow musician, the idea of using tempo, rhythm, and sound in composition has always resonated with me. If reading a sentence aloud doesn't please the ear, throw that sentence in the pit (or at least give it another pass or two).

2. I was beginning to think no one but the big names really makes a living from literary fiction. Every author bio I see these days ends with "teaches writing at whatever the hell university."

If it's not too much to ask, what percentage of that living is from book sales vs speaking engagements? Have you had much luck optioning your work for film adaptations or any other creative licensing schemes?

Very interesting. Thanks for this.