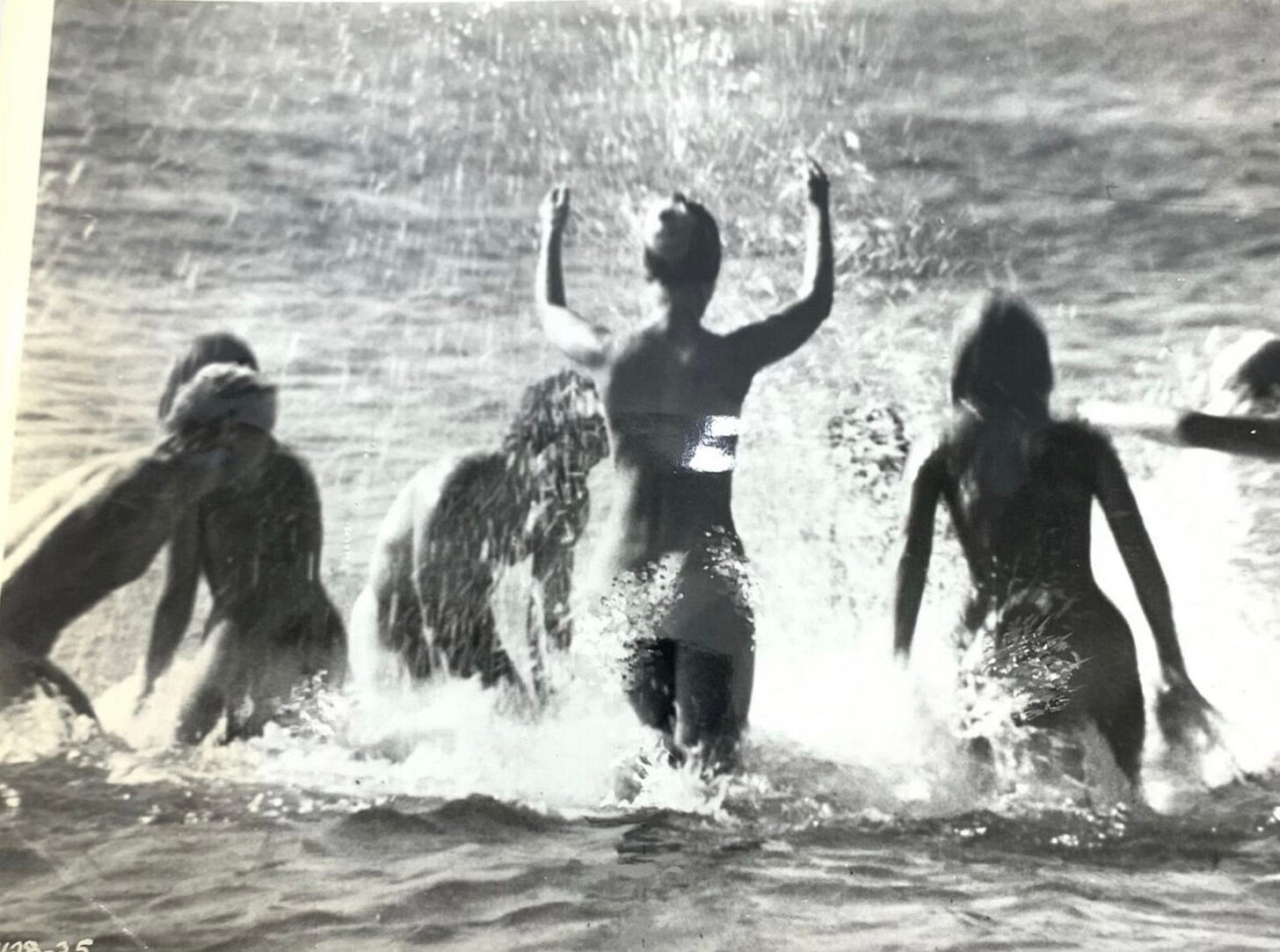

Lake Cavanaugh, 1999

I don’t know whether it feels good or bad to look back on a memory like this and realize that it lies more than a quarter of a century in the past. I was young enough, then, that I hadn’t yet lived that long, and so “a quarter of a century” felt like a long, long time.

It was a summer night, and it was dark, and the only light was from our fire on the lake shore. We all went skinny dipping in the black water that went down forever. I could barely swim—still am not any good at it—so I stuck close to the dock and held onto it often, a chip of object reality in a cold weightless void. When we got out, we stood around the fire with blankets and big towels wrapped around ourselves, and J. opened his blanket and the light was red on his naked body, and he was the only thing, the only thing visible in a whole, unseen world.

The road we would drive up to the cabin was a two-lane highway that ran from I-5 through a couple of shitty little towns, out across the farmland and into the foothills. Just outside the town of Bryant, the road passed perilously close to the corner of an old white house. The house had obviously existed much longer than the highway had. Over the decades, the road got wider to accommodate more cars, bigger cars, but the house held its ground. Your car would pass its sharp white corner by mere inches. If you were stupid and crazy, you could stick your hand out the window and slap the house as you sped by. I always wondered what it must be like to sleep in there, in that room, with the rural rush of a highway on the other side of your wall, the doppler bend of fast objects in motion hushing you down into a dream.

Recently I drove out to the lake, just to see what was still the same. The house is gone now. The highway is a little wider.

Currently reading: Notebook by Tom Cox